Your Secrets Are Safe: How Browsers’ Explanations Impact Misconceptions About Private Browsing Mode

Your Secrets Are Safe: How Browsers’ Explanations Impact Misconceptions About Private Browsing Mode Yuxi Wu et al., World Wide Web Conference 2018

With this paper, I’m taking it back to 2018. I found this paper by Yuxi Wu et al. particularly interesting because it centers around a feature of browsers that a good amount of people use and/or is sometimes recommended as a way of staying safe on the internet: “private browsing.” In their work, they focus specifically on the disclosures users see when they open a new window in a browser’s private mode and some of the misconceptions users have about the privacy guarantees when using these modes.

Setting the Stage

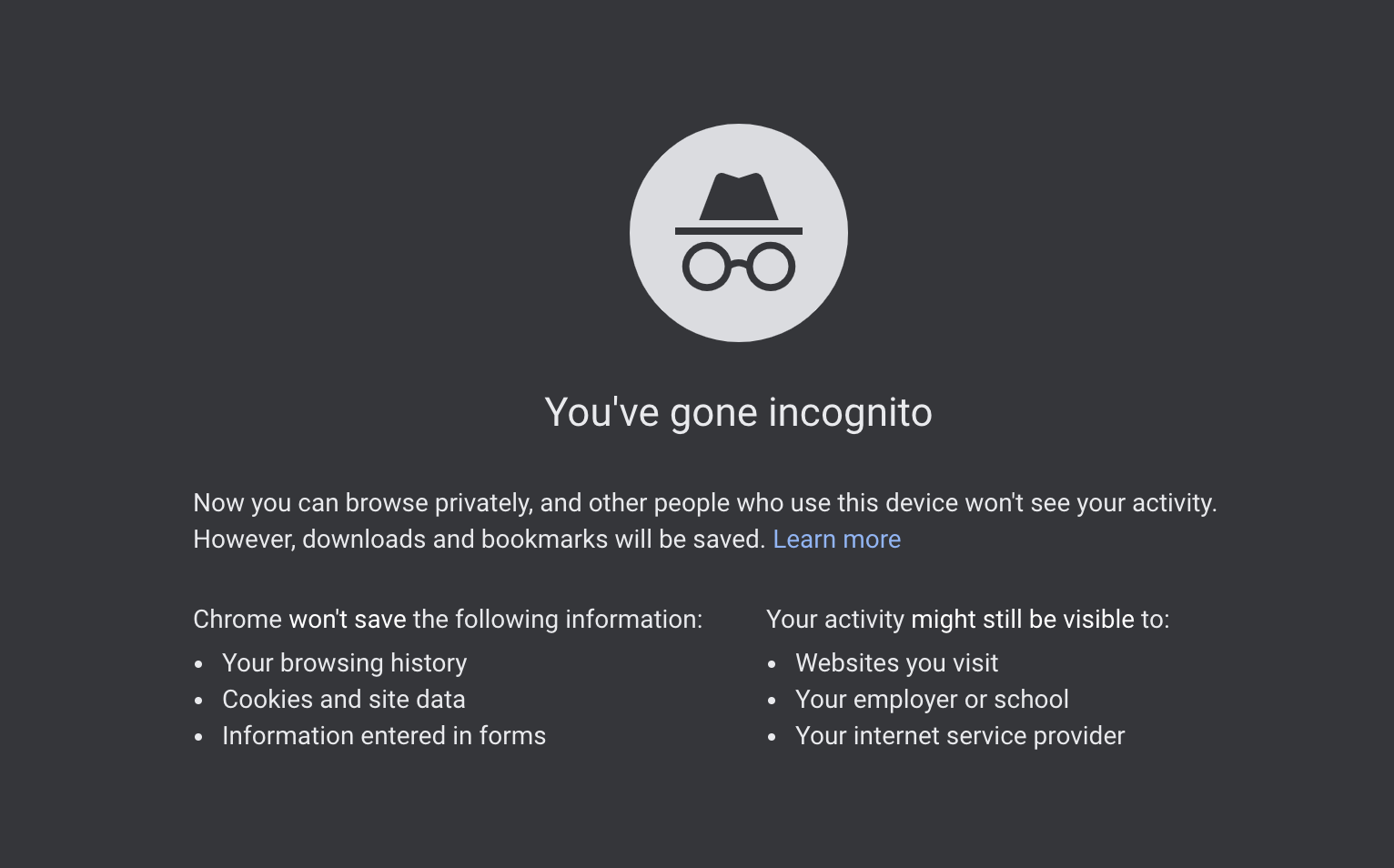

If you’re not familiar with private mode, it’s a feature that each of the major browsers has that is geared towards protecting users against local privacy threats such as someone seeing your browser history on a shared device. Each browser calls their version of private mode something different but they are more or less the same. When using private mode, a user’s browser history is not stored after a session is closed, cookies are cleared after the session is closed, and temporary files are deleted. To reiterate, private mode does not protect against remote threats. The two exceptions to certain degrees are Opera’s Free VPN that has to be enabled by the user and Firefox’s Enhanced Tracking Protection.

Meet the browser: Onyx

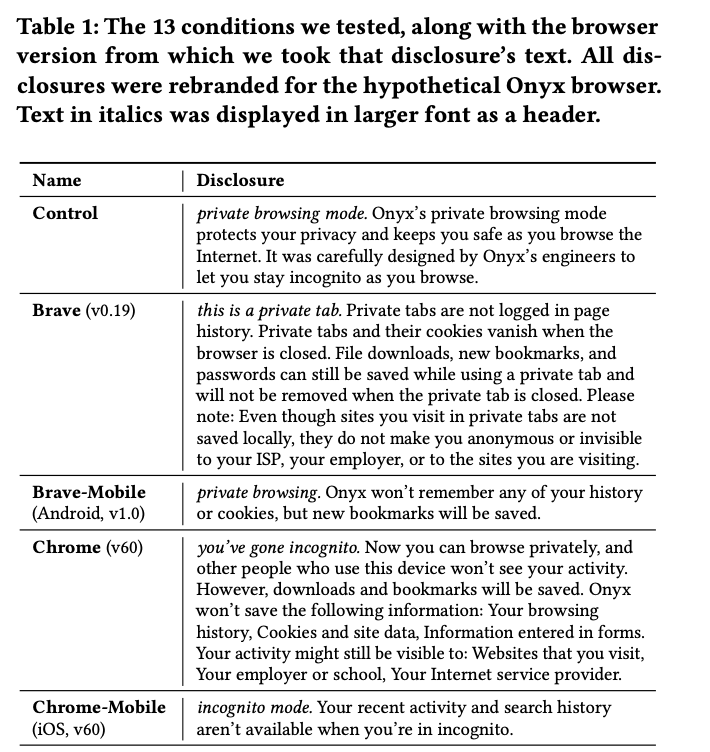

To understand the misconceptions users have surrounding private browsing Wu et al. designed an experiment where they had users imagine a new browser called Onyx. With this “new browser”, they presented a simulated browser window where they used the disclosure for each of the following browsers: Brave, Chrome, Edge, Firefox, Opera, Safari and a control that vaguely described some privacy guarantees. They also tested the mobile versions of each of the majors browsers except Edge. Their experiment followed a between subject’s design where each study participant only saw one of the 13 disclosure. If you’re doing some math and you’re like that doesn’t add up to 13, you’d be right. Wu al. tested two versions of the Chrome browser (59 and 60) because at the time Google had recently changed their disclosure.

After showing each participant was shown the disclosure for their condition, they were presented with twenty browsing scenarios. 16 of these scenarios were designed to measure the differences participants perceived between private mode and standard mode. In the other four scenarios, participants were asked multiple choice questions in which they were asked to make relative comparisons between the two modes. An example question is “How will the speed at which webpages load compare in standard vs private browsing modes?” After seeing each scenario, participants were asked a yes or no question and then asked how confident they were in their answers (Very Confident, Confident, Somewhat confident, Not at all confident). Finally, they were asked why they chose a particular answer.

At the very end of each session, Wu et al. collected demographic information, information on their browser usage and usage of private mode.

Specifically, they set out to answer the following research questions:

- How do each of the six desktop disclosures compare to the control?

- How do mobile versions of disclosures compare to the disclosure in the same browser’s desktop version

- How does the recently redesigned Chrome disclosure compare to the previous disclosure.

Results

In total, they recruited 460 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk and found that approximately ~97% of participants used Google Chrome for desktop browsing and that 80% of participants used private browsing at least some of the time. They found that the top six reasons users used private browsing were 1) hide browsing, especially visits to adult websites 2) prevent targeted ads and search suggestions 3) achieve “safer” browsing 4) prevent browsers from saving login-related information 5) avoid cookies 6) accommodate intentional or unintentional use by others.

To understand the impact each of the disclosures had on a participant’s understanding of private mode, Wu et al. created a correctness and confidence score. The correctness score was just the total number of scenarios that the participant answered correctly excluding the six scenarios where the correct answer was browser dependent. The confidence score was the sum of the confidence ratings for the same 14 scenarios. Using those two scores they created regression models using demographic and study-related characteristics. In the end, they found that most of the disclosures had no significant impact on a participant’s understanding of what private mode does or doesn’t do. Specifically, only the participants who were shown one of the two versions of Chrome for desktop disclosure answered more correctly than the control group. They also found that the mobile disclosures were less successful than the control.

(Non-)Misconceptions

Wu et al. denoted scenarios where over 20% of participants across disclosures answered the question about private mode incorrectly as misconceptions. While they found there were a lot of misconceptions there were a good amount of scenarios that almost all participants got correct. Some examples are 97% of participants correctly realized that files downloaded in private mode would remain on the computer after the session has ended and 90% of participants knew that photos viewed in the browser during private mode would not be cached for quicker loading during future sessions. On the flip side, participants both over and underestimated the protection private mode offers. The most notable overestimate was that 22%, 37%, and 23% of participants respectively believed that ISPs, employers and the government could not track them when they used private mode. In terms of underestimates, 30% of participants incorrectly thought that their searches could be associated across sessions.

Bringing it to 2020.

Since this research was conducted in 2017, I decided to take a look at the disclosures for Brave, Safari, Chrome and Firefox to see if they had made any significant changes and if so what. What I found is that each of the four browsers had changed their disclosures for both mobile and desktop versions except for Safari. In the case of Chrome, Google has opted to use the same disclosure across both the mobile and desktop version which I think is a positive change. By using the same disclosure for both versions, it’s possible to rule out that misconceptions were derived simply from seeing a different version on a different platform. Overall, the mobile versions of each of the browsers tested in 2017 had far less text describing what private mode did/did not do. While that still proves to be the case, Brave-Mobile (and Chrome-Mobile by default) has made massive improvements in terms of providing additional information on the privacy guarantees when using private mode on their mobile browser.

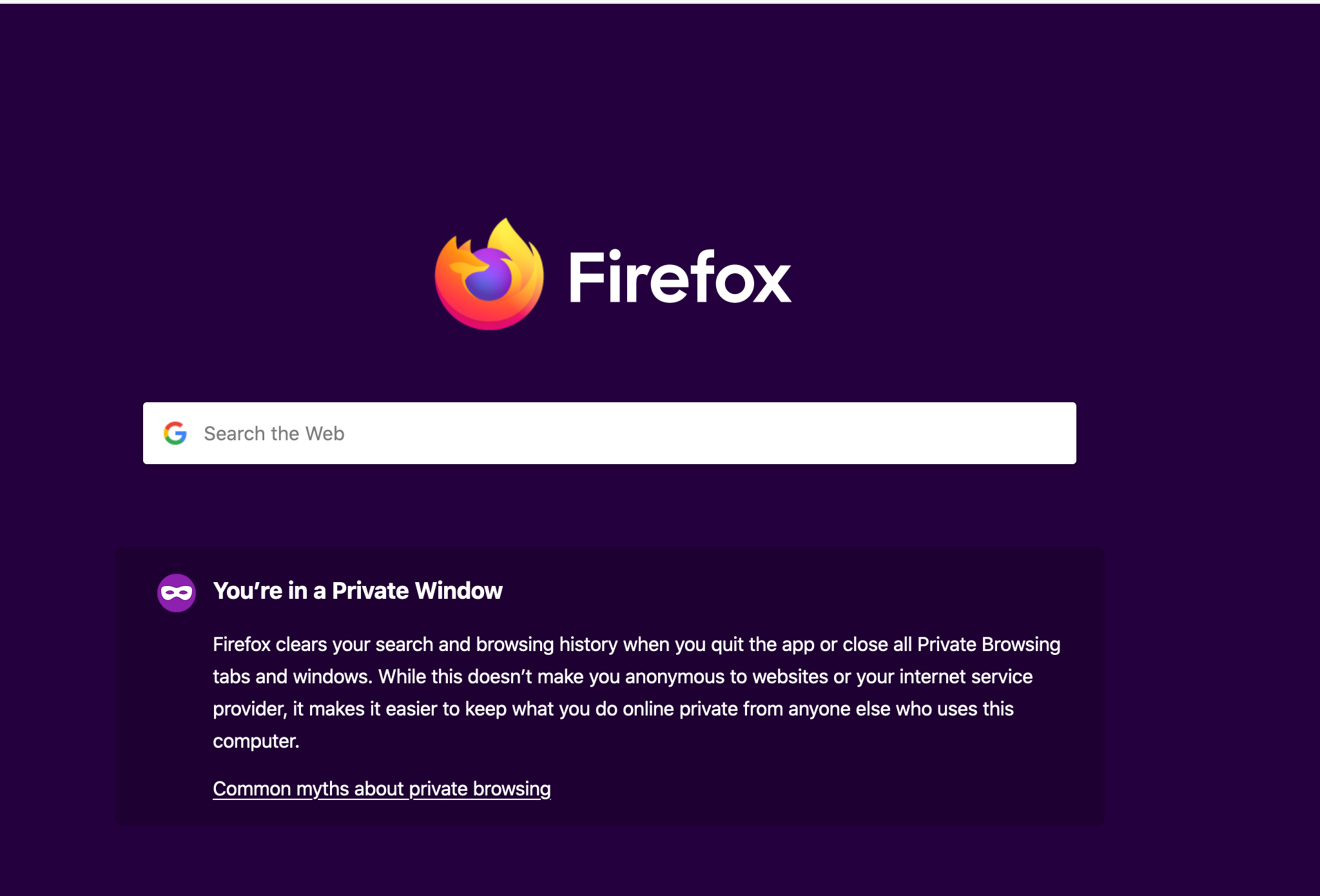

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the changes Firefox has made. As you can see in the figure above, Firefox provides users a link to a page that dispels some of the myths about private browsing. I think just having a link is a big step in the right direction and gives users an easily accessible resource to get more information on what guarantees they have when using private mode even if it takes a bit more work.

Wrapping Up

It seems like most browsers are making efforts to improve the disclosures users see when entering private mode. Nevertheless, there are still some areas that they could improve on. It would be interesting to see if the results by Wu et al. would be the same given the current set of disclosures.