Moving Beyond Set-It-And-Forget-It Privacy Settings on Social Media

Moving Beyond Set-It-And-Forget-It Privacy Settings on Social Media Mainack Mondel et al., Conference on Computers and Communication Security 2019

The last paper that I looked at from CCS is a bit different than the four previous papers that I’ve summarized that have focused on the usability of libraries, methods, and technologies. This work by Mandal and his collaborators centers around user privacy on Facebook. There is also a bit of machine learning, but I promise you there won’t be too much math. With that said, let’s dig in!

Privacy on Facebook

The main thread throughout the paper is that a user’s preference with whom to share data (in this case Facebook posts) may change over time. In the case of Facebook, the number of friends a user has now could be many times higher than when a particular post was first made. As a result, the privacy settings that were originally used on a post may not be appropriate given a user’s new connections.

As a primer for those that don’t use Facebook, Facebook allows users to control who sees their posts through the Audience Selector. Mainack et al., do a great job in comparing it to traditional role-based access control where the roles are as follows:

- public: anyone can see it

- friends+: the user’s Friends plus the friends of some/all of those friends

- friends: the user’s Facebook friends

- custom: a user-specified subset of Facebook friends

- only me: only the user

#Goals

In the work by Mandal et al., they try to build an understanding of Facebook privacy attitudes and and practices and how those may change over time through a user study with the goal of translating those findings into a human-in the-loop privacy management system.

User Study

In addition to understanding the privacy practices and attitudes of Facebook users, they conducted the user study to get data to be used later to test a predictive model.

Recruitment and Demographics

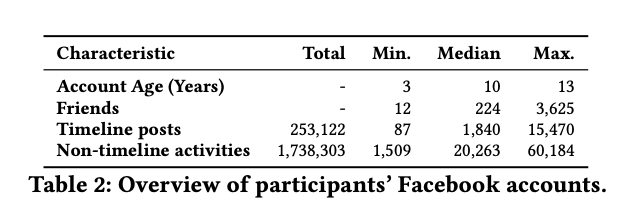

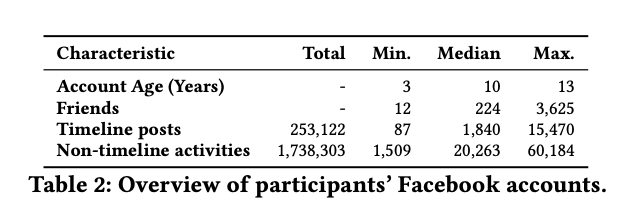

They recruited participants using Amazon MTurk who were at least 18 years of age and located in North America. In total, they had 101 participants. Over 2/3 of their participants identified as female. 46% of participants fell in the 25-34 age range which was consistent with the overall age distribution of Facebook users in 2018 [1]. 87% of participants identified as white. In terms of Facebook usage, approximately 90% of participants reported using Facebook daily. More info about their usage can be found in the table below.

Getting Data and Labels

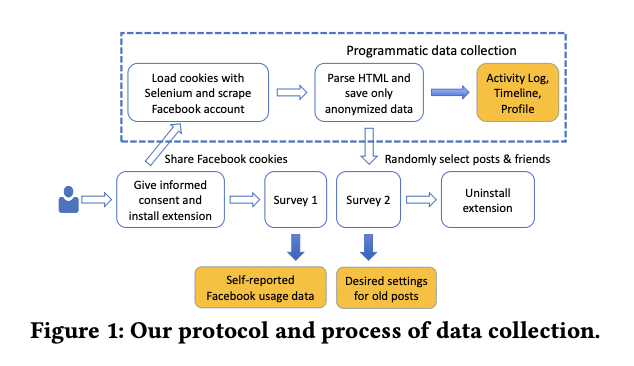

In order to collect participant data, they had each participant download a browser extension. The extension collects an anonymized version of their full Facebook timeline as well as their Facebook activity log. This was accomplished by the browser extension sharing their session cookie with a server at University of Chicago which used Selenium to download the relevant parts of the participant’s timeline and activity log. In the paper, Mandal et al. provide more detail than I can put in this summary about how they try to collect the data in privacy preserving way. A diagram of the protocol that they used can be seen in the figure below.

After they collected each participant’s data, they did a two-part survey. In Part 1, they randomly selected five posts from a participants timeline. Then they showed them the posts current privacy settings and if they had changed the posts settings or considered changing them. Last, they asked if the participant wanted to change those settings or keep them the same and why. In part two, they used those same posts but they showed six of the participant’s Facebook friends who could see the post. They also asked whether or not the participant wanted to continue sharing that post with that person or if they didn’t care. The six friends were picked from six categories of interaction where interaction was measured through things like number of words exchanges via posts and comments and the number of reactions the participant and their friend gave each other on posts. More information on those six categories can be found in the table below.

In addition to the post experiment, participants completed a survey which asked about their overall Facebook usage and their use of Facebook’s privacy features.

Findings from the Data

In examining the longitudinal data, they found that friends (the default setting) was the most used privacy setting. The reason that this is important is that because the number of friends each participant had increased over time they were therefore sharing these older posts with more and more people. Another interesting but intuitive finding from the survey they administered was that a participant’s life changes impacted their privacy settings. The most common personal changes that were cited were relationship changes and childbirth.

Shifting gears to the two post experiments, Mandal et al. found that the majority (~75%) of posts didn’t require any changes, but 63.5 participants wanted to change the privacy settings on at least one post. Interestingly enough, the changes that participants wanted to make were roughly split between increasing and decreasing the audience size.

Mandal et al. also explored the correlation between participants’ privacy preferences and the interactions they had with a particular user. They found that participants were more likely to share posts with friends whom they had a high degree of recent interactions with than those who they had not recently interacted with. That makes a lot of sense; however, the inverse wasn’t true. Participants also wanted to “definitely keep sharing” posts with 35% of the friends who they hadn’t had any interaction with in the past year. When they examined the qualitative data that was collected, Mandal and his collaborators found that 35% fell into the categories of family member or close friend.

Let’s Do Some prediction

As mentioned earlier, the ultimate goal was to help users have the right privacy settings for posts that were made in the past no matter how old they are. Because the amount of posts can be large the only reasonable course of action would be to use some type of automated system. Cue Machine Learning!

Problem formulation

Mandal et al. formulated the problem as binary classification where the two classes were limit sharing and do not limit sharing. They also stress that they would want this to be a human-in-the loop system and not a “fully automatic post manager.”

Data and Features

The features that they used were composed of information gathered through the survey responses, user information, posts statistics, content, and audience. For post statistics, they used things like the number of likes and comments, whether or not another user was tagged, etc. They also used NLP methods to extract content-level features from the text of posts.

Evaluation

Mandal et al. evaluated several models such as Decision Trees, Logistic Regression, and Support Vector Machines. The results of these models were tested against two baselines. The first was a random classifier where they randomly show posts to users. The second baseline uses the level of interaction between the user and their friend and predicts limit sharing for friends with low levels of interaction.

For their experiments, they used two datasets. One called the post dataset containing 389 posts and another called the friend-post dataset containing 2336 labels. Each dataset has different goals. In the post dataset, they try to predict whether a user should decrease the audience of a post. In this friend-post dataset, they try to predict whether or not a specific friend’s access to the post should be removed. The difference in the datasets is that the friend-post dataset contains six times as much data (and therefore labels) because it has the decisions made for the six friends that were randomly shown.

The metrics that they used for evaluation were the precision and for limit sharing. In addition, they also include precision at K which is the precision after predicting the top K results as positive. They included precision at K because they could vary the number of posts shown to a user.

Results

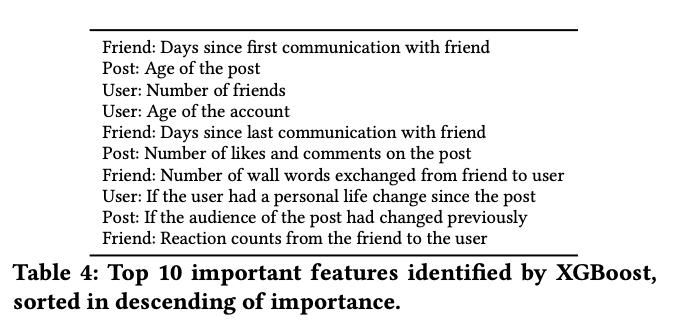

On the friend-post dataset, they found that the XGBoost model had the highest precision at K performing the best for even low values of K. In examining the precision-recall curve, they found that when K was set to 30 they found that the precision-recall area under the curve (PR AUC) was 0.493 which was much higher than the 0.118 PR AUC achieved by the interaction baseline model. The reason 30 was used as the value of K was that it corresponds with the underlying distribution of limit sharing. Mandal et al. also tried to find the most predictive features. In the table below, you’ll see the top 10 features for the XGBoost model.

For both datasets, they analyzed which posts their classifier was wrong. One of their findings was that a significant number of misclassified posts were those that linked to external content like images or videos. Mandal et al. didn’t collect features specific to a posts’ external content for privacy reasons and because it wasn’t supported by current literature. They also found that another source of inaccuracy for misclassified posts (16%) was that they didn’t have features specific to participant’s friends. An example provided in the paper pertaining to why a participant would share a post with a particular friend was “I think she likes articles about animals.”

Wrapping Up

In this work, Mandal et al. find that for Facebook users access control is usually set-it and forget-it but that has longer term implications as a user’s life changes, the number of posts they have increase, and the number of friends they have rises. Moreover, predicting whether or not to limit sharing of a post with a particular through the use of machine learning models is more effective than simply relying on the interaction between users.

References

[1] Statista. 2018. Number of Facebook users by age in the U.S. as of January 2018 (in millions). https://www.statista.com/statistics/398136/us-facebook-user-agegroups/. (Last accessed in August 2019).